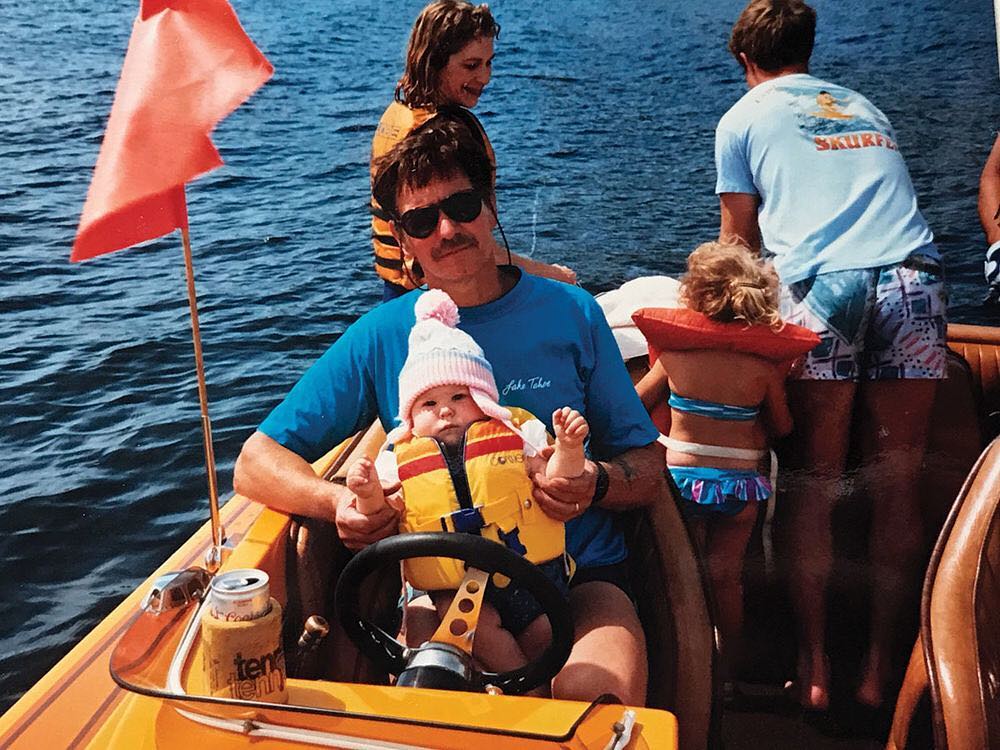

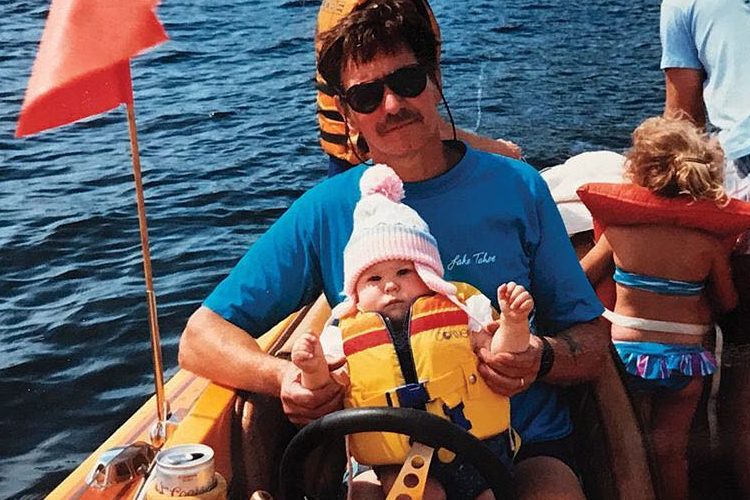

Horse racing has long been called the “sport of kings.” With its million dollar thoroughbreds, caviar hors d’oeuvres and Kentucky Derby style, it wears this moniker well. Of course, it’s not the only well-heeled sport. With waterfront mansions; sleek, pricey inboard boats; and far-flung international ski sites, the sport of water skiing is no slouch. As a matter of fact, with participation slipping, many wonder if our sport’s royal road to riches is keeping everyone else outside the kingdom walls.

Is our sport solely the domain of one percenters and lakefront homeowners who can pony up $50,000 to $100,000 for a top-of-the-line boat, or is there room for everyday nine-to-fivers with used skis and borrowed gear who chip in gas money for a ride on their buddy’s ’90s -era Supra Comp?

“Water skiing’s been called the sport of kings, but I don’t know if we should apologize for that or run from that,” says Jim Emmons, president of the Water Sports Industry Association. “It is what it is.

“Let’s turn that questions around,” Emmons says. “The folks who water ski are generally in the upper echelon of education and earnings potential. But think what it would be like if it was accessible to anybody; think what our waterways would be like. You’d be taking turns in a long line to get a pull every moment of every day.”

Although Emmons admits that he, along with others at towed water sports companies, would love to see the 5 million active water skiers grow to 10 million, he wonders about capacity. He questions if perhaps it’s better to have slow and steady growth instead of a rapid increase. He does have a point. For example, if it cost only $1,000 to field a NASCAR team, every gear head with a piggy bank would be clogging the racetracks below the Mason-Dixon line and west of the Mississippi. The same thing goes for golf, snow skiing, surfing and countless other sports for that matter. No athlete would have much fun with jam-packed links, ski resorts or board-to-board waves.

Are Water-Skiing Costs Pushing People Out?

Let’s face the facts. Boats aren’t cheap. Skis cost money. And tournaments don’t pay for themselves. But how much is too much? Is water skiing pricing itself out of reach of the common athlete? Have the costs become such a barrier to entry that a limited number of new skiers are able to enter the fold?

The Sports & Fitness Industry Association’s Water Skiing Participation Report 2013 turned up some interesting – and sobering – statistics. Total participation in water skiing in the United States dropped 5.6 percent from 2007, when 5.9 million participated, through 2012, which had fewer than 5 million skiers. Participation by casual skiers dropped by 3.9 percent, whereas core skier participation dropped by 8.9 percent. What’s the reason for declining numbers?

“Skiing is becoming more and more elite because its costs are out of control,” says Wisconsin skier Zach Jachowicz, an average-joe skier who hits the water about two or three times per week. “I for sure agree that there’s a ton of engineering and money that goes into the skis, bindings and boats, but some of these prices are outrageous.”

Jachowicz told us that when he and his family attend tournaments, they feel almost like outsiders, partly because the world of competitive water skiing is a close-knit-community but also because it’s a seemingly very affluent community. To Jachowicz, it seemed almost like a clash of classes. And keeping up with all the newest equipment is almost impossible. “It’s not cheap to keep up with the latest and greatest gear,” he says. “I purchased my first new ski, a Radar Vice with double Vector bindings, last year at the Malibu Open. The last new ski I had before that was an HO Extreme from maybe 2001.”

What Does it Cost?

Longtime coach and high-end equipment retailer Steve Schnitzer, who invented the wing and the adjustable fin, says that rising costs are definitely pushing people out. “I’m continually hearing from clients about the price of a boat, with most new boats over $60,000.” New slalom boats can retail anywhere from the $50,000s, $60,000s or higher, depending on options. Wakeboarding and crossover boats – for those who like to keep a foot in both worlds or just to keep the family happy – can run as high as $120,000 or more. Yowza!

Is that something most people can afford? According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the median household income for 2013 was $52,100, which is down somewhat because of the recession. That means that half of all household incomes were above that number, and half were below.

Although a boat is the single largest investment a person will make in the sport, Schnitzer helps us sort out some of the other expenses. “A top-of the line blank ski with a fin can start around $1,940,” he says. Add in shipping charge, and you’re at roughly $2,000. From there, you’ve got hard shells at around $650. The ski case is another $70. Add in a rope for $90 and a nice handle for about $110. Now you need a vest for $150 and gloves for $60. “To show up and ski behind your friend’s boat is over $3,000,” he says. “Sure, you can buy used and cut your cost down. But that’s without even a bathing suit.”

There are other, less obvious, costs that can also chomp up your bank account. Since skiers tend to crave private lakes to sharpen their skills, access to those private lakes becomes an issue. Take the Rocky Mountain Water Ski Club at Sweetwater Ranch in Dostero, Colorado for example. Members get access to the private course, the clubhouse, hot tub, picnic areas and the 19-foot ski boat. The price? More than $200,000. Of course, by becoming one of only 15 members, you also become a one-fifteenth owner of this exclusive skiing wonderland.

The topic of escalating costs burned up the forums on ballofspray.com recently. “I think the main factor which has driven up the cost of skiing is the increase in price or lack of lakefront property,” says lifelong skier David Stowe, who hails from Mooresville, NC, near Lake Norman. “Young people who would become lifelong skiers are unable to buy in at higher property values. Thus, they can’t conveniently ski and really never pick up the sport. Slowly over time, the number of skiers decreases, and the cost of certain necessities, like ski boats, increase due to economies of scale.”

How to Ski on the Cheap (AKA Buddies with Boats)

Ok, so water skiing is expensive. And many of its ardent participants aren’t hurting for dough. Which begs the question: How can the rest of us get in on the fun? Is it possible to ski on the cheap?

Absolutely, according to Dave Ross, a skiing fanatic and resident “onthecheap expert” who told us how the other half does it. He lives in Litchfield, Minnesota, an hour west of Minneapolis, on the 550-acre Lake Ripley, where he’s been president of the Lake Ripley Improvement Association since 2002. “I live on a public lake within the city limits and have a mint ’91 Ski Centurion Falcon Barefoot on my lift,” he says. “The boat sees lots of family duty pulling tubes, wakeboarding and barefooting and is used for general boating and driving fun. I bought it in ’99 from my dad for $13,000 and the maintenance has been minimal. I don’t ski buoys with the Centurion, but having now owned it for 15 years, I’d say that is family fun on the cheap.”

But he doesn’t stop there. Ross has a group of buddies with boats and resources to help each other feed their skiing passions. “I split another ski site with my buddy Bob 10 miles from home,” he says. “We call it ‘the swamp’ [Hoff Lake]. We pay a landowner a total of $750 [$375 each] to keep a dock, boat lift and ski boat extended from his property.” They installed two slalom course. Bob’s ’87 MasterCraft ProStar 190 pulled the guys for years until 2010, when Ross bought a 2000 Ski Nautique 196 with 84 hours on it and PP classic for $17,000. “We still ski that boat today and will for many years to come,” he says.

Boat Co-Ownership and Cable Parks

One way to defray the costs of boat ownership is to purchase one with a group of friends, Everyone pays; everyone helps with cleanup; everyone buys fuel – sounds like a good deal. And spreading the cost of a boat purchase out among four to eight people puts boat ownership well within reach.

Take Richard Doane’s group in Burien, Washington, for example – four guys who jointly purchased a 2011 Malibu Lxi. “The LLC we formed for our ‘club’ boat has been a great thing now for three seasons,” Doane says. “As with any group, you need to have some rules in place, and expectations spelled out in the beginning. People typically rise up to the expectation that you set.”

But make sure there are solid expectations. “I had four friends who purchased a mid-1990s Ski Nautique, and it turned into a huge mess for them,” says Rod Long, an ex-Canadian ski junkie and soon-to-be lakefront homeowner at Ski Texas south of Houston. “In the end, the boat got sold, and a couple of friendships were ruined. That was my sign to figure out how to do it on my own when I could afford to.” Long says he plans to be on the water daily as soon as he’s into his almost-completed home 50 feet from his boat.

USA Water Ski executive director Bob Crowley sees other ways to overcome costs and increase participation. “One of the best alternatives for those who can’t afford a boat is the growth of cable parks around the country,” he says. “Yes, right now they’re primarily catering to wakeboarding, but it can also work with water skiing there too.”

Schnitzer agrees. “What ski companies and the industry need to do to get more people into the sport is to introduce more cable parks,” he says. “Ski all day for $30 or $40 bucks. Correct Craft is now investing in cable parks. They see the handwriting on the wall. A cable park is economical; it costs next to nothing. It’s like going to the mountain [snow skiing] for a lift ticket.”

“Cable parks are coming online faster and faster,” Emmons says. “One’s just been approved outside Washington D.C. They’re opening up all over the country, and they can be a feeder system for watersports. You can get a tow without having to buy a boat.”

Ski Clubs: Our Best Hope

“Clubs,” Crowley says. “That’s how new people can get interested in the sport. They can connect to the clubs in their area who have their own boat. That’s the biggest hurdle to getting started,” He stresses that clubs provide great camaraderie and make trying out the sport immensely more affordable.

Taryn Garland, the new USA Water Ski program development coordinator, emphasizes the importance of clubs in the life of the sport. “Introducing new people to the sport is where clubs really come into play,” she says. “They all pool their resources for the common good. They chip in for gas. You can ask for help and be open to networking. If you get plugged into a club, they usually have extra equipment in their garage. Clubs are like family.”

Garland carved many a lake as part of Wisconsin’s Mad-City Ski Team for 11 years – and five national titles – and it’s there in show skiing that she sees a great opportunity to increase the accessibility and visibility of the sport. “You want a way to involve as many people as possible,” she says. “Sometimes in three event, there are only so many people who can ski at a time. Show ski teams allow many people to participate.” Those skiers will often go on to compete in three-event tournaments.

The Future

How do we stem loss of participation due to costs? Everyone has an opinion, but it’s encouraging to hear that all facets of the industry – from the boat and product manufacturers, to USA Water Ski, to instructors, to athletes – are responding.

“A lot of our top-level water skiers have moved to private lakes, and our sport is no longer as much in the public eye as it was 15 years ago,” Crowley says. “Knowing that we’re all connected, we’re encouraging our big-time athletes to reach out on Twitter, Instagram and open up their life a little bit for people to see.” USA Water Ski is also looking to more strategically transition collegiate skiers back into the American Water Ski Association, offering “starter skits” with exclusive discounts on gear to collegiate teams.

“The future of our sport depends on everybody being able to work together and growing it together,” Garland says. To that effect, USA Water Ski is celebrating its 75th year with a campaign celebrating “Life on the Water.” The whole purpose is to get more people on the water and build the base of the sport through grass-roots clubs, basic skills clinics, membership drives, dealer days and any other way to increase visibility. For a list of ski clubs in your area, visit usawaterski.org.

With almost 5 million people water skiing in the U.S., there is a lot of life left in this sport. Cost doesn’t have to be a barrier to entry. Whether it’s through cable parks, boat co-ownership, dealership promotions or joining a ski club, there are many ways to make it work and get people to see the allure of a “life on the water.”

“I wouldn’t hesitate to sell off all my other toys in order to keep playing and having fun on the water,” says Rod Long. “My motorcycle would probably be the first to go.” Jachowicz echoes that sentiment. “I would do anything to continue to pursue skiing,” he says.

This article originally appeared in the April 2014 edition of Waterski Magazine.